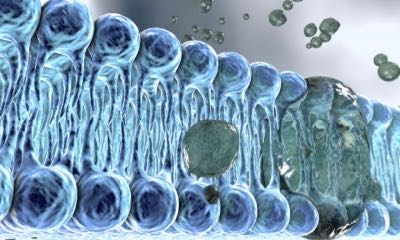

The human body is full of bacteria. Believe it or not—this is a good thing. Living microbial communities play a vital role in human health. These “microbiomes” can be found in the gut, the skin, the mouth, the respiratory tract, and more.

Over the past couple decades, scientists have made numerous discoveries about how the microbiome works and the many ways it benefits health. Most of this work focused on the intestine, but research suggests that some of the knowledge we’ve gained could benefit other microbiomes in the body.

Probiotics, living microorganisms that benefit gut health, emerged from the initial scientific discoveries about the microbiome and quickly became one of the most popular supplements consumed in the world. As the science developed, the focus broadened to include prebiotics, the variety of fibers that act as gut microbiome fertilizer.

Recently, a new biotechnology has started to hit the shelves: postbiotics.

In this article, we’ll discuss everything you need to know about these beneficial byproducts.

What are Postbiotics?

Postbiotics are the byproducts of the natural metabolic process (fermentation) of probiotic bacteria. They include various types of molecules such as short-chain fatty acids, peptides, organic acids, enzymes, and more. They offer many of the same benefits that probiotics do. But there’s one key difference. Postbiotics are non-living bioactive metabolites. While probiotics are live strains of bacteria.

There are three similar words that frequently come up when discussing the microbiome, each with its own unique definition: probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics. Let’s clarify the difference between each term:

- Probiotics: Unlike the following two terms, probiotics are living microorganisms. Basically, they’re the “good” microbes living in your gut. You can bring more probiotics into your body by eating probiotic foods such as yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi—or quality probiotic supplements.

- Prebiotics: Like all living things, your microbes need to eat. Prebiotics are the substances that the microbes in your body consume for sustenance. These include starches, inulin, and pectin—all forms of complex carbohydrates.

- Postbiotics: When probiotic bacteria metabolize their food, they create various byproducts. These byproducts can offer you some of the same benefits as the microbes themselves and are called postbiotics.

Postbiotics don’t require the use of live bacteria. They’re stable, safe, and have a broad range of application in health products. You might start to notice them in nutraceuticals, foods, supplements, and even high-end skincare products.

Let’s dive a little deeper into some of the practical applications of postbiotics.

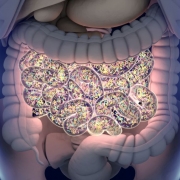

The Gut Biome: A Vital Microbial Ecosystem

One of the most well-researched healthy bacterial communities is the gut biome. When your gut microbiome is healthy, it helps your body digest food, regulate immune function, guard against harmful pathogens, and support cognitive functions through the gut-brain axis. Although the exact composition of each person’s gut biome is different, they are all composed of the same types of microorganisms: bacteria, viruses, and fungi.

When people talk about a functioning microbiome, they often use descriptors like “healthy” and “balanced.” So, what does it actually mean for your microbiome to be healthy? A healthy gut biome is one in which there are plenty of the good microorganisms and inconsequential amounts of the bad. This is exactly how probiotics work. They improve gut health by increasing the number of beneficial bacteria and reducing the number of harmful bacteria to make your microbiome healthier.

Basically, a healthy or balanced microbiome is able to do its job—and if it’s not, you’ll probably notice.

An unbalanced gut biome is called dysbiosis and can have a number of adverse health effects. These include irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), autoimmune disorders, and even new allergies.

Needless to say, it’s important to care for your gut biome.

Postbiotics do many of the same things as probiotics—without live strains of bacteria. They support the growth and the function of healthy bacteria in your gut microbiome, which supports your health. This means that postbiotics shift the composition of the microbiome towards a healthier, more balanced ecosystem. Postbiotic metabolites also have direct benefits for the gut. They’ve been shown to:

- Regulate digestion and absorption of nutrients

- Support the intestinal barrier

- Suppress bad bacteria

- Fight pathogens

- Play a role in the gut-brain axis

- Reduce irritation in the gut

So how do you increase the amount of postbiotics in your gut? Like with all things health-related—it starts with your diet.

Dietary Sources of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Postbiotics

Your body naturally produces postbiotics as the bacteria in your gut metabolize their food and create waste. You can increase the amount of postbiotics in your system by increasing the amount of probiotics and prebiotics that you consume. The formula is pretty simple: the more food (prebiotics) you supply to the microorganisms (probiotics) in your gut biome, the more byproducts (postbiotics) they will create.

Foods that are rich in probiotics are typically fermented foods, which include:

- Kefir

- Cottage cheese

- Kimchi

- Kombucha

- Buttermilk

- Sauerkraut

High fiber foods tend to be the best source of prebiotics. Some examples of prebiotic-rich foods include:

- Barley

- Garlic

- Oats

- Seaweed

- Flax seed

- Onions

If you are looking to directly supply your body with more postbiotics, those supplements exist as well. But some of the most interesting applications for postbiotics are those that wouldn’t be practical for probiotic bacteria.

Let’s discuss how the benefits of postbiotics translate to another important microbiome: your skin flora.

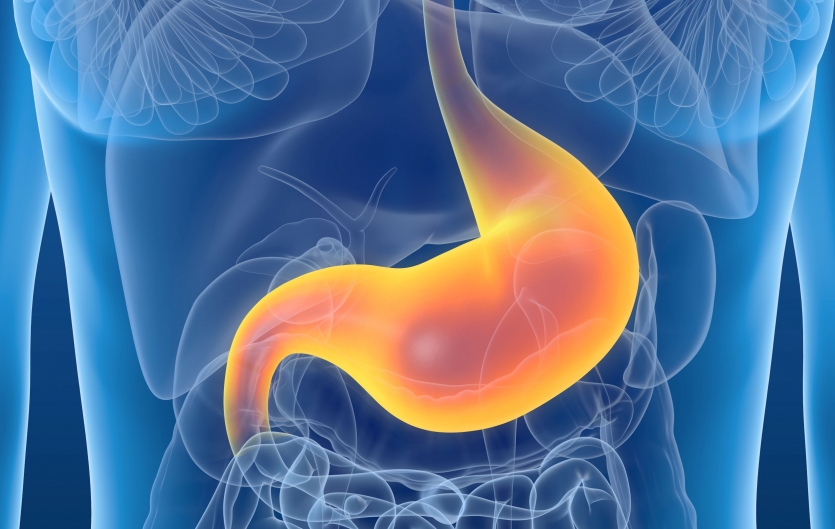

Skin Microbiome: Your Body’s Natural Barrier

The skin microbiome is the community of microorganisms; bacteria, fungi, and viruses, that live on the skin. Just like the gut microbiome, this microbial community is much more than a passive, fellow traveler. The skin flora plays a vital role in maintaining skin health and even other aspects of health. Here are some of the roles your skin microbiome is involved in:

- Protection of the Skin: A healthy skin flora inhibits the growth of potential invaders and pathogens on the skin.

- Skin Barrier Function: Your skin microbiome acts as a functional barrier, helping the skin retain moisture, improve hydration, and reduce skin sensitivity.

- Immune Support: The skin flora interacts with the immune system to support balanced inflammatory responses.

- Tissue Healing: A balanced skin microbiome promotes tissue repair and cell turnover on the skin while preventing infection in vulnerable areas.

- Skin Health and Beauty: A strong and healthy skin flora is associated with a balanced complexion and clear, moisturized skin.

Dysbiosis occurs when the skin microbiome is out of balance or disrupted. This can lead to a variety of skin issues like acne, redness, dermatitis, and infections. In fact, skin sensitivity and problematic skin are related to a damaged skin microbiome.

Maintaining a healthy skin flora involves taking care of your skin, avoiding harsh chemicals in skincare products, and choosing products that support a healthy microbial balance on the skin.

That’s where postbiotics come in.

Postbiotics can support the good bacteria on the skin by feeding it with beneficial metabolites. That’s why many skincare products now include postbiotics. Using postbiotics on the skin will support all the benefits we mentioned above. They can improve the skin’s barrier function, reduce acne and skin sensitivity, improve hydration, balance the pH of the skin, and even reduce signs of aging like visible fine lines and discoloration.

In Summary

Science has discovered so much in recent years about the symbiotic microbial communities in the human body. But we are still barely scratching the surface.

Although much of the research has been focused on the gut microbiome, the biotechnology of postbiotics represents a new frontier. Where the discoveries made about the gut microbiome can be applied in completely new contexts.

The years to come will undoubtedly lead to more discoveries and a better understanding of the body’s less-explored microbiomes in overall health.