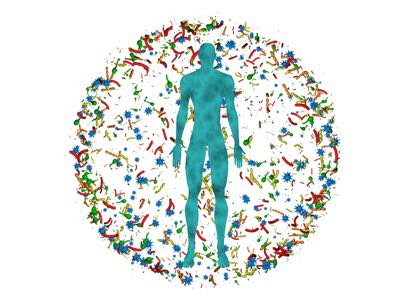

Brushing your teeth might help change your mood or prepare you for a good night’s sleep. It’s simple advice for good oral health. But the reality is that your mouth is one of your body’s most complex places. Partly because it’s the gateway to your digestive tract. And with everything you put into your mouth on a day-to-day basis, you’re inviting and hosting scores of different types of life—collectively known as the oral microbiome—inside your oral cavity.

It might sound a little scary, but there are colonies of bacteria everywhere inside your mouth. On your teeth. In your gums. On your tonsils. Beneath your tongue. On the inside walls of your cheeks.

The oral microbiome contains over 700 prevalent species of bacteria, according to the American Society of Microbiology. And all of these various bacteria come to hang out and play their part in your oral and overall health.

That’s right. There’s a big connection between oral health and your long-term health. But what do the different types of bacteria living inside your mouth provide in terms of functionality? What influences the makeup of these varying types of microbes? And perhaps most importantly, what’s the key to maintaining a healthy balance of oral bacteria?

Science helps break it down.

Why Oral Bacteria Exists

The fact is, bacteria and other microbes are almost inescapable. They live everywhere around you, on you, and inside you. That’s prompted experts to refer to these microbes as “permanent guests.”

The oral microbiome is no different. Various bacteria and microbes contribute to health—positively and negatively. And this complexity has been a topic of focus among cell biologists, microbiologists, and immunologists over the last decade. These microbial communities create a fascinating world for experts to explore. Purnima Kumar, professor of periodontology at Ohio State University, said every time a person drinks a glass of water, they’re swallowing millions of bacteria.

Kind of gross. Also fun to think about, right? But it’s not much fun for the residents of the oral microbiome.

There’s a battle raging inside your mouth. It’s a life-or-death fight for space and food. And the outcome is important to you. Some bacteria in what is also called your biofilm help protect your mouth and maintain the health of your teeth and gums. Others create issues for your dental health.

The ongoing fight between the good and bad sides can be easily swayed based on things you do. That includes behaviors—like diet and poor oral hygiene—as well as recurring health problems. One interesting development scientists have figured out is your overall oral health is generally influenced by your mother’s oral health. That’s because you’re more likely to be born with similar bacteria.

That’s right—you weren’t born with teeth, but you’re born with oral bacteria.

It’s Time to Start Caring About the Composition of Your Oral Microbiome

You know that gross feeling when you wake up every morning? With the film on your teeth and your breath not at its best—to put it kindly? What if that was permanent? No thanks.

The easy answer to this issue might be to remove all the bacteria in your mouth so you don’t have to feel that way. But if you wiped away all the bacteria in your mouth, you would be ridding yourself of those that work on your behalf, too.

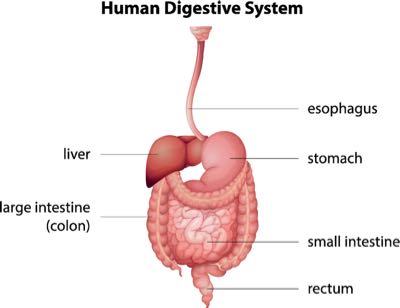

Certain bacteria fighting on your team can help your breath stay away from nasty territory. On top of that, some bacteria of the oral microbiome work to break down foods in an enzymatic reaction that starts with your saliva.

Some strains of bacteria like Streptococcus and Neisseria are linked in studies to the maintenance of esophageal health. And Neisseria has proven to play a part in the breakdown of toxic substances like tobacco smoke.

There are bad guys in there, too. And they can have their say both in the short-term and the long-term health of your mouth. So, the important thing is to create a balance of bacteria that is beneficial to your health. Just like you can do in your gastrointestinal tract.

It’s all about space and food. That starts with good hygiene. Experts will tell you what your parents have said all along: brush and floss to keep bacteria under control. That’s why when you let oral care slide for a while, things in your mouth can get dicey. Bacteria levels can rise, which could cause issues for your teeth and gums.

There are other factors you might not think of—like saliva. It helps wash away lingering bits of food and provides protection from acids produced by bacteria. But some medications can reduce the flow of saliva in your mouth. Be aware of this if you take some decongestants, antihistamines, and antidepressants.

Your diet also plays a role in the health of your mouth and your oral microbiome. That means concentrating on a healthy diet that supports the growth of good bacteria instead of bad ones. Adding an oral probiotic also might be useful to support a healthy balance for your oral microbiome. You’ll find more tips later on in the story.

What Kind of Bacteria Live in Your Mouth?

Don’t worry, there’s no way to cover all the types of bacteria in your oral microbiome on one page. There’s simply too many. Covering the hundreds and hundreds of different species would require a full book.

But here are some common types of bacteria you should be familiar with:

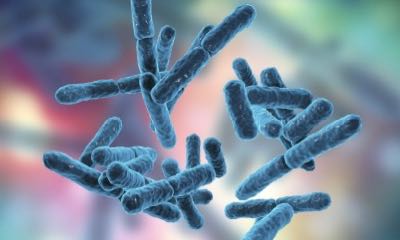

- Streptococcus: One of the largest players in the oral bacteria community, there are several different strains that fall under the Streptococcus family. Usually they are oval-shaped chains of bacteria cells. And some can cause issues for your teeth. Streptococcus mutans, for example, is a potential pathogen that can convert sugar to lactic acid. And that acid buildup is bad for your teeth.

- Porphyromonas gingivalis: This is one type of bacteria you don’t want to see show up. Luckily it isn’t usually present in a healthy oral microbiome. Avoid it to maintain the health of tissues and bone structures that support your teeth.

- Lactobacillus: These strains are long, rod-like bacteria that have thick cell walls. Like Streptococcus strains, Lactobacillus helps change lactose (a milk sugar) into lactic acid. This means more acids that shouldn’t be allowed to linger in your mouth. But Lactobacillus is a beneficial bacteria for your gut, which is why it’s in many probiotic products.

- E. Coli: Most E. coli in the human body is found in your guts, but a trace amount of the bacteria is also part of the oral microbiome. Thankfully, not all E. coli strains are alike. And these aren’t the same as the ones you hear about on the news from contaminated foods.

The oral microbiome’s residents are created equal. In fact, different strains of the Streptococcus family actually are helpful. Streptococcus salivarius K12 aids in fighting bad breath. Like you read above, Neisseria helps breakdown bad substances like cigarette smoke, and some strains help break down food.

It’s not currently possible to design your bacterial mix to be purely good. So, maintaining a healthy balance in your mouth microbiome is what’s important. And there are several ways you can support this healthy balance.

Tips to Maintain a Healthy Balance of Oral Bacteria

There will always be a variety of neutral, harmful, and helpful oral bacteria renting out space in your mouth. That’s just the reality of the situation. Don’t fret, though. There are simple answers for keeping your oral microbiome in good shape.

First and foremost, it’s about maintaining the necessary level of oral hygiene. Brushing—twice a day—and daily flossing keeps bacteria at bay.

Your lifestyle and diet also have a big impact on the bacteria in your mouth. A healthy, whole-food diet that’s mostly plant-based is a great start. You also need to avoid things that stimulate the growth of bad bacteria. Sugar is a big source of food for oral bacteria. Also stop smoking—or, better yet, never start. Nicotine is damaging to your oral microbiome. Stress is also as bad for your bacteria as it is for you.

Oral probiotics can also help add more beneficial bacteria to the microbiome, too. Researchers have found that supplementing with oral probiotics can be a useful tool in supporting and maintaining the health of your mouth. Oral probiotics are generally chewables or in tablets of various forms that allow the bacteria to set up shop in your mouth and adapt to their new environment.

The gateway to your body is one of the most complex parts of you. Understanding what’s going on inside your mouth and your oral microbiome can help maintain your long-term health. The oral microbiome is the initial line of defense for your overall health, so start taking steps to care for it every day.

References

https://jb.asm.org/content/192/19/5002

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2768665/

https://www.jnj.com/innovation/4-things-scientists-know-about-the-bacteria-in-your-mouth

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5960472/

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/320232.php

https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/adult-health/in-depth/dental/art-20047475

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0966842X0500257X

https://www.health.harvard.edu/press_releases/heart-disease-oral-health

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1287824/

https://www.hyperbiotics.com/blogs/recent-articles/7-surprising-ways-to-support-oral-health

https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/newly-discovered-microbe-keeps-teeth-healthy

https://askthedentist.com/oral-probiotics/

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/beat-bad-breath-keep-mouth-bacteria-happy/