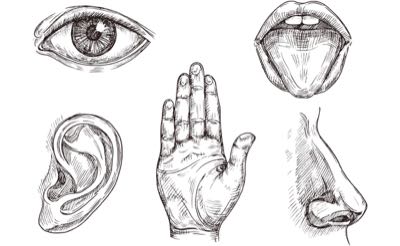

As soon as you get out of bed, your five senses are hard at work. The sunlight coming in through your window, the smell of breakfast, the sound of your alarm clock. All these moments are the product of your environment, sensory organs, and your brain.

The ability to hear, touch, see, taste, and smell is hard-wired into your body. And these five senses allow you to learn and make decisions about the world around you. Now it’s time to learn all about your senses.

Purpose of the Five Senses

Your senses connect you to your environment. With information gathered by your senses, you can learn and make more informed decisions. Bitter taste, for example, can alert you to potentially harmful foods. Chirps and tweets from birds tell you trees and water are likely close.

Sensations are collected by sensory organs and interpreted in the brain. But how does information like texture and light make it to your body’s command center? There is a specialized branch of the nervous system dedicated to your senses. And you may have guessed that it’s called the sensory nervous system.

The sensory organs in your body (more on these a bit later) are connected to your brain via nerves. Your nerves send information via electrochemical impulses to the brain. The sensory nervous system gathers and sends the constant flood of sensory data from your environment. This information about the color, shape, and feel of the objects nearby help your brain determine what they are.

What are Your Five Senses?

There are five basic senses perceived by the body. They are hearing, touch, sight, taste, and smell. Each of these senses is a tool your brain uses to build a clear picture of your world.

Your brain relies on your sensory organs to collect sensory information. The organs involved in your five senses are:

- Ears (hearing)

- Skin and hair (touch)

- Eyes (sight)

- Tongue (taste)

- Nose (smell)

Data collected by your sensory organs helps your brain understand how diverse and dynamic your surroundings are. This is key to making decisions in the moment and memories, as well. Now it’s time to go deeper on each sense and learn how you gather information about the sounds, textures, sights, tastes, and smells you encounter.

Touch

Your skin is the largest organ in the body and is also the primary sensory organ for your sense of touch. The scientific term for touch is mechanoreception.

Touch seems simple, but is a little bit more complex than you might think. Your body can detect different forms of touch, as well as variations in temperature and pressure.

Because touch can be sensed all over the body, the nerves that detect touch send their information to the brain across the peripheral nervous system. These are the nerves that branch out from the spinal cord and reach the entire body.

Nerves located under the skin send information to your brain about what you touch. There are specialized nerve cells for different touch sensations. The skin on your fingertips, for example, has different touch receptors than the skin on your arms and legs.

Fingertips can detect changes in texture and pressure, like the feeling of sandpaper or pushing a button. Arms and legs are covered in skin that best detects the stretch and movement of joints. The skin on your limbs also sends your brain information about the position of your body.

Your lips and the bottoms of your feet have skin that is more sensitive to light touch. Your tongue and throat have their own touch receptors. These nerves tell your brain about the temperature of your food or drink.

Taste

Speaking of food and drink, try to keep your mouth from watering during the discussion of the next sense. Taste (or gustation) allows your brain to receive information about the food you eat. As food is chewed and mixed with saliva, your tongue is busy collecting sensory data about the taste of your meal.

The tiny bumps all over your tongue are responsible for transmitting tastes to your brain. These bumps are called taste buds. And your tongue is covered with thousands of them. Every week, new taste buds replace old ones to keep your sense of taste sharp.

At the center of these taste buds are 40–50 specialized taste cells. Molecules from your food bind to these specialized cells and generate nerve impulses. Your brain interprets these signals so you know how your food tastes.

There are five basic tastes sensed by your tongue and sent to the brain. They are sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami. The last taste, umami, comes from the Japanese word for “savory.” Umami tastes come from foods like broth and meat.

A classic example of sweet taste is sugar. Sour tastes come from foods like citrus fruits and vinegar. Salt and foods high in sodium create salty tastes. And your tongue senses bitter taste from foods and drinks like coffee, kale, and Brussels sprouts.

A formerly accepted theory about taste was that there were regions on the tongue dedicated to each of the five tastes. This is no longer believed to be true. Instead, current research shows each taste can be detected at any point on the tongue.

So, during meals or snacks, your brain constantly receives information about the foods you eat. Tastes from different parts of a meal are combined as you chew and swallow. Each taste sensed by your tongue helps your brain perceive the flavor of your food.

At your next meal, see if you can identify each of the five tastes as you eat. You’ll gain a new appreciation for your brain and how hard it works to make the flavor of your food stand out.

Sight

The third sense is sight (also known as vision), and is created by your brain and a pair of sensory organs—your eyes. Vision is often thought of as the strongest of the senses. That’s because humans tend to rely more on sight, rather than hearing or smell, for information about their environment.

Light on the visible spectrum is detected by your eyes when you look around. Red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet are the colors found along the spectrum of visible light. The source of this light can come from a lamp, your computer screen, or the sun.

When light is reflected off of the objects around you, your eyes send signals to your brain and a recognizable image is created. Your eyes use light to read, discern between colors, even coordinate clothing to create a matching outfit.

Have you ever gotten ready in the dark and accidentally put on socks that don’t match? Or realized that your shirt was on backwards only after you arrived at work? A light in your closet is all you need to avoid a fashion faux-pas. And here’s why.

Your eyes need light to send sensory information to your brain. Light particles (called photons) enter the eye through the pupil and are focused on the retina (the light-sensitive portion of the eye).

There are two kinds of photoreceptor cells along the retina: rods and cones. Rods receive information about the brightness of light. Cones distinguish between different colors. These photoreceptors work as a team to collect light information and transmit the data to your brain.

When light shines on rods and cones, a protein called rhodopsin is activated. Rhodopsin triggers a chain of signals that converge on the optic nerve—the cord connecting the eye to the brain. The optic nerve is the wire that transmits the information received by the eye and plugs directly into the brain.

After your brain receives light data, it forms a visual image. What you “see” when you open your eyes is your brain’s interpretation of the light entering your eyes. And it’s easiest for your brain to make sense of your surroundings when there is an abundance of light. That’s why it’s so challenging to pick out matching clothes in the dark.

To improve your vision, your eyes will adjust to let in the maximum amount of light. This is why your pupils dilate (grow larger) in the dark. That way, more light can enter the eye and create the clearest possible image in the brain.

So, give your eyes all the light they require by reading, working, and playing in well-lit areas. This will alleviate stress on your eyes and make your vision clearer and more comfortable. Also try installing nightlights in hallways so you can safely find your way in the dark.

Hearing

The scientific term for hearing is audition. But this kind of audition shouldn’t make you nervous. Hearing is a powerful sense. And one that can bring joy or keep you out of danger.

When you listen to the voice of a loved one, your sense of hearing allows your brain to interpret another person’s voice as familiar and comforting. The tune of your favorite song is another example of audition at work.

Sounds can also alert you to potential hazards. Car horns, train whistles, and smoke alarms come to mind. Because of your hearing, your brain can use these noises to ensure your safety.

Your ears collect this kind of sensory information for your brain. And it comes in sound waves—a form of mechanical energy. Each sound wave is a vibration with a unique frequency. Your ears receive and amplify sound waves and your brain interprets them as dialogue, music, laughter, or much more.

Ears come in a variety of shapes and sizes. But they share similarities. The outer, fleshy part of the ear is called the auricle. It collects the sound waves transmitted in your environment and funnels them toward a membrane at the end of the ear canal.

This is called the tympanic membrane, or more commonly, the ear drum. Sound waves bounce off the tympanic membrane and cause vibrations that travel through the drum. These vibrations are amplified by tiny bones attached to the other side of the ear drum.

Once the sound waves enter the ear and are amplified by the ear drum, they travel to fluid-filled tubes deep in the ear. These tubes are called cochlea. They’re lined with microscopic hair-like cells that can detect shifts in the fluid that surrounds them. When sound waves are broadcast through the cochlea, the fluid starts to move.

The movement of fluid across the hair cells in the ear generate nerve impulses that are sent to the brain. Amazingly, sound waves are converted to electrochemical nerve signals almost instantaneously. So, what begins as simple vibrations becomes a familiar tone. And it’s all thanks to your sense of hearing.

Smell

The fifth and final sense is smell. Olfaction, another word for smell, is unique because the sensory organ that detects it is directly connected to the brain. This makes your sense of smell extremely powerful.

Smells enter your body through the nose. They come from airborne particles captured while you breathe. Inhaling deeply through your nose and leaning towards the source of an odor can intensify a smell.

Inside your nose is a large nerve called the olfactory bulb. It extends from the top of your nose and plugs directly into your brain. The airborne molecules breathed in through your nose trigger a nervous response by the olfactory bulb. It notices odors and immediately informs your brain.

Higher concentrations of odor molecules create deeper stimulation of the brain by the olfactory bulb. This makes strong scents unappealing and nauseating. Lighter fragrances send more mild signals to your brain.

You need your sense of smell for a variety of reasons. Strong, unpleasant smells are great at warning your brain that the food you are about to eat is spoiled. Sweet, agreeable smells help you feel at ease. Odors given off by the body (pheromones) even help you bond with your loved ones. Whatever the scent, your brain and nose work as a team so you can enjoy it.

Senses Work Together to Create Strong Sensations

It’s rare that your brain makes decisions based on the information from a single sense. Your fives senses work together to paint a complete picture of your environment.

You can see this principle in action the next time you take a walk outside.

Reflect on how you feel when you’re out walking. Take note of all the different sensations you experience. Maybe you see a colorful sunset. Or hear water rushing over rocks in a stream. You might touch fallen leaves. Paying attention to the convergence of your sense means you’ll find it hard to go for a stroll without experiencing something new.

Here’s a few recognizable examples of your senses working together:

Smell + Taste = Flavor

Just like a walk outdoors brings together several of your senses, a good meal can do the same. Flavor is a word often used to describe the way food tastes. But flavor is actually the combination of your senses of taste and smell.

The five tastes talked about earlier don’t accurately describe the experience of eating a meal. It’s hard to assign sweet, salty, sour, bitter, or umami to something like peppermint or pineapple. But your brain doesn’t have to interpret flavor from your taste buds alone. Your sense of smell helps out, too. This is called retronasal olfaction.

When you eat, molecules travel to the nasal cavity through the passageway between your nose and mouth. When they arrive, they’re detected by the olfactory bulb and interpreted in the brain. Your taste buds also collect taste information. This sensory data from your nose and tongue is compiled by the brain and perceived as flavor.

With the tongue and nose working together, the experience of eating peppermint is more than just a bitter taste. It’s a cool, refreshing, and delicious treat. And a slice of pineapple isn’t only sour. It’s tangy, sweet, and tart.

You can see how smell affects flavor by plugging your nose while you eat. Cut off the path makes you notice a significant decrease in flavor. Conversely, you can get more flavor out of your food by chewing slowly. That way more of its scent can be detected in the nose.

Senses and Memory

Certain smells can bring powerful memories to mind. This is an interesting phenomenon. Studies suggest that the position of the olfactory bulb in the brain is responsible for smells triggering emotional memories.

That’s because the olfactory bulb connects directly to the brain in two places: the amygdala and hippocampus. These regions are strongly linked to emotion and memory. Smell is the only one of your five senses that travels through these regions. This could explain why odors and fragrances can evoke emotions and memories that sight, sound, and texture can’t.

What Happens with Sensory Loss?

Sometimes people experience decreased sensation or the absence of a sense altogether. If this affects you, know you’re not alone. There are many people that experience life just like you do.

Examples include the loss of sight or hearing. Blindness or deafness can begin at birth or be developed later in life. It does not affect everyone in the same way. The important thing to realize is that you can live a full and rich life as a deaf or blind person.

Often, if one of the five senses is reduced or absent, the other four will strengthen to help the brain to form a complete picture of the environment. Your sense of smell or hearing might be heightened if you experience blindness or low vision. If you are deaf or hard of hearing, your senses of touch and sight may become keener.

There are great tools available to those experiencing sensory loss. Talk to someone you trust if you need help with your own decreased sensation. And be respectful of others who live without certain senses.

Support Your Five Senses with Healthy Habits

Your senses add variety and texture to your life. And it’s important to protect their health. It’s perfectly normal to experience some decline in sensation with age. But there are steps you can take to preserve your senses and take care of your body, too.

Here are four important tips:

- Be cautious with your hearing. Long-term exposure to loud noises can damage the membranes in your ear that create sound. Wear earplugs at boisterous concerts and when operating noisy power tools. Listen to music at lower volume. Take the necessary precautions so you can enjoy good hearing throughout your life.

- Keep your eyes safe from sun damage by wearing sunglasses. You can also help support your vision by eating foods with healthy fats, antioxidants (especially lutein and zeaxanthin), and vitamin A.

- Protect your touch-sensitive skin with sunscreen and moisturizers. And drink enough water to avoid dehydration.

- Develop a taste for a diet loaded with vitamins and minerals. Eat whole foods, fruits, and lots of veggies. Supplementation is also an easy, practical way to add to your already healthy diet, too.

You can put your five senses to work with activities like gardening, walking, and cycling. Take in the sights, sounds, and smells of your surroundings. Make healthy choices so you can continue enjoying life through your senses.

About the Author

Sydney Sprouse is a freelance science writer based out of Forest Grove, Oregon. She holds a bachelor of science in human biology from Utah State University, where she worked as an undergraduate researcher and writing fellow. Sydney is a lifelong student of science and makes it her goal to translate current scientific research as effectively as possible. She writes with particular interest in human biology, health, and nutrition.

References

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/11/181105160852.htm

http://www.fifthsense.org.uk/psychology-and-smell/

https://medium.com/@SmartVisionLabs/why-vision-is-the-most-important-sense-organ-60a2cec1c164

http://udel.edu/~spfefer/art307/project3/hearing.html

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279408/

http://www.fifthsense.org.uk/smell-taste-and-flavour/

https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-the-sense-of-taste-works-1191869

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sense#Sight

https://www.visiblebody.com/learn/nervous/five-senses

https://learning-center.homesciencetools.com/article/five-senses-lesson-projects/

http://pillowlab.princeton.edu/teaching/sp2015/slides/Lec16_Audition_Chap9B.pdf

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-ap1/chapter/audition-and-somatosensation/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/mechanoreceptor

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-biology/chapter/somatosensation/

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2012/01/120111103354.htm

https://www.health.harvard.edu/aging/how-our-senses-change-with-age