Dry, cracked skin is more vulnerable to environmental effects. On the other hand, plump and hydrated skin functions how it should, sealing out irritants and locking in moisture.

And though you may not have heard of them, ceramides are one of the most important components of your skin. They’re masters at protecting and helping retain moisture. Recently, ceramides have even become a key ingredient in many skincare products. These creams and moisturizers fortify your natural ceramide levels to help support your skin’s health.

What Are Ceramides?

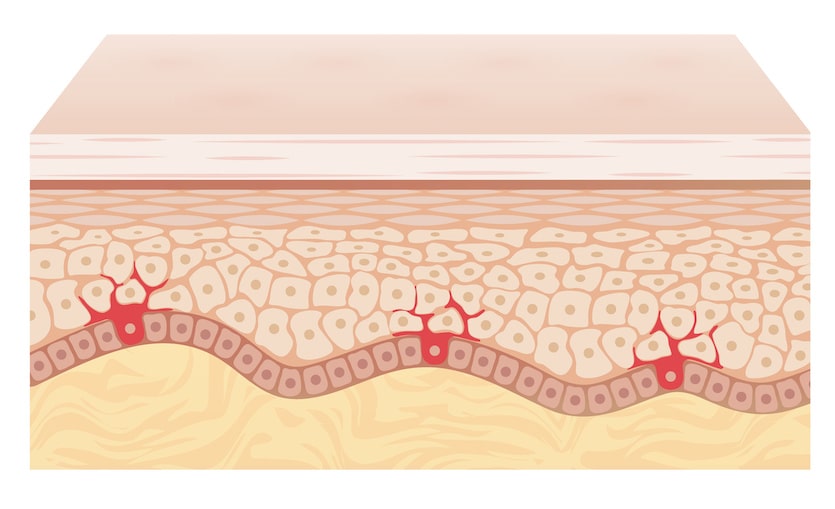

Ceramides are lipids that make up about 50% of your skin’s composition and play a primary role in the function and appearance of your skin barrier. The rest of your skin consists of layers of cells that are constantly dying out and refreshing themselves with new cells. You’re likely familiar with the epidermis and dermis skin layers, but it may surprise you that these layers of tightly packed cells rely on a biochemical “seal” for the skin to function properly. This makes ceramides every bit as important to your epidermis as your skin cells themselves. Think of ceramides as the glue that holds your skin cells together to form a functional barrier. The healthier this barrier is the more it protects, even keeping your skin better hydrated.

When applied topically, ceramides can support moisture levels and keep the skin barrier healthy. Ceramides can be synthetic (man-made) or natural, like the ones found in your outer layers of skin. To really understand what they are, let’s dip into the biochemistry. Don’t worry—we’ll make it quick and easy.

All ceramides are made up of a compound called sphingosine—a chain of carbon atoms with an amino acid bonded to it. When sphingosine binds to other fatty acids, it forms ceramides. There are 12 distinct types of ceramides, named ceramide 1-12, based on the type of sphingosine it is and the kind of fatty acid that binds to it.

Why do Ceramides Matter?

Skin problems may emerge if your ceramides are not functioning properly. Age and sun damage can reduce the effectiveness of your natural ceramides. Eventually, as ceramide levels are depleted, a weakened skin barrier can lead to drier, more problematic skin. The metric that cosmetic scientists use to measure skin hydration is called transepidermal water loss (TEWL). Dry or irritated skin has higher TEWL, and reduced water-binding capacity.

Ceramide-rich skincare products help to support and balance your skin, and reduce TEWL, even after ceramide levels have diminished.

The skin-nurturing benefits of ceramides can:

- Fortify your skin’s protective barrier

- Help your skin retain moisture

- Rejuvenate your skin’s appearance

- Support plumper, smoother-looking skin with fewer visible fine lines and wrinkles

The Right Ceramide Products for You

Proper packaging keeps your ceramide products performing at their best. As you look for quality ceramide products, avoid glass jars or clear packaging. Many of the most popular “antiaging” skincare ingredients are sensitive to oxidation and can lose their effectiveness when exposed to light and air. So, look for tubes or opaque bottles with pumps and airtight dispensers.

If a product contains ceramides it will be listed in the ingredients. Also look for ceramide-related ingredients like phytosphingosine and sphingosine. All of these support your skin’s natural production of ceramides when applied topically. And it may be even easier—with such sought-after benefits, many products display these ingredients front and center on the package.

Ceramides are beneficial for all types of skin, even sensitive skin, because they are a natural component of your epidermis. If you’re looking to upgrade your skincare routine or are still a novice in the world of skincare, try a product with ceramides and experience the benefits of moisturized, healthy-looking skin!