Flex Your Knowledge About Joints

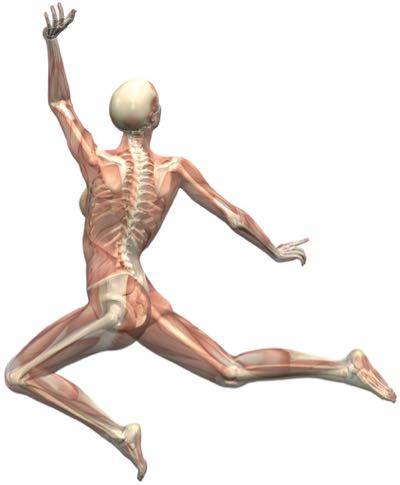

It’s hard to imagine a life without joints. They spring into action the moment you roll out of bed. Joints facilitate little movements like brushing your teeth and tying your shoes. And they also allow you to clap, dance, and play.

Thank your joints for helping you find this article. Whether you’re at your desk or scrolling through your phone, joints make movement (like keystrokes and texting) possible.

Joints play an important part in everyday life. But it might not be easy to know if your joints are in good health. So, pause for a moment to learn about joints and easy ways to keep them in shape.

The Role of Joints

Joints are the skeletal hinges that make movement possible. Simply defined, a joint is the area where two bones connect, or make contact. They turn a rigid skeletal frame into a dynamic and flexible body.

Your joints are powered by muscle to move your body. And there are two main ways your joints move. When the bones in a joint move away from each other (like when you spread out your fingers and open your hand) it’s called extension. Flexion happens when your bones are brought closer together (making a fist).

Types of Joints

Not all the places your bones connect are the same. And there are three main types of joints. Grouped together by their range of movement and material composition, they are: fibrous (immovable), cartilaginous (slightly moveable), and synovial (freely moveable).

Fibrous

This joint may initially be hard to identify. They don’t look or function like you’d think a joint would. Fibrous joints (or fixed joints) are permanent connections between two bones. The easiest fibrous joints to identify are the sutures of the skull.

Your skull is made up of large, flat bones that fused together over time. But your skull was not always rock solid. A newborn’s is soft and moldable in order to safely exit the birth canal. Flexible bones slide over each other during delivery and return to their original position in the days following birth.

The flat bones of the skull then grow larger over time and become connected by thick, fibrous tissue. This joint is called a suture. Once settled in their permanent location, sutures ossify (turn to bone). These joints are completely immobile.

Teeth are another example of fibrous joints. Also called gomphoses, the joints between teeth and their sockets are welded together by periodontal tissue.

Cartilaginous

Like the name suggests, these joints are made up of cartilage links between bones. But not the squishy cartilage that makes up your ears and nose. This joint cartilage is incredibly strong and can withstand significant pressure.

A cartilaginous joint is only slightly moveable. One example is the pubic symphysis that connects the left and right pubic bones and stabilizes the pelvis. However, when a woman gives birth, this joint permits enough movement to widen her pelvis for delivery.

There are also cartilaginous joints between every vertebra in your spine. Individually, joints between vertebrae can move very little. But each slightly moveable cartilaginous joint across multiple vertebrae allows for dramatic movement—think about bending over to touch your toes.

This important type of joint also function to absorb impact. Cartilage discs cushion the spine and maintain its flexibility while you walk, jump, and dance.

Unlike their fibrous siblings, cartilaginous joints will never turn to bone. They remain mildly flexible and work together to provide strength and mobility throughout the body.

Synovial

When you think of joints, you probably picture the synovial type. These are the connections between bones that make up your shoulder, hip, knee, and more. Synovial joints are free-moving and can extend and flex in several directions.

There are several different kinds of synovial joints. Most notable are the hinge, pivot, and ball-and-socket joints. These names describe how the joints work in your body:

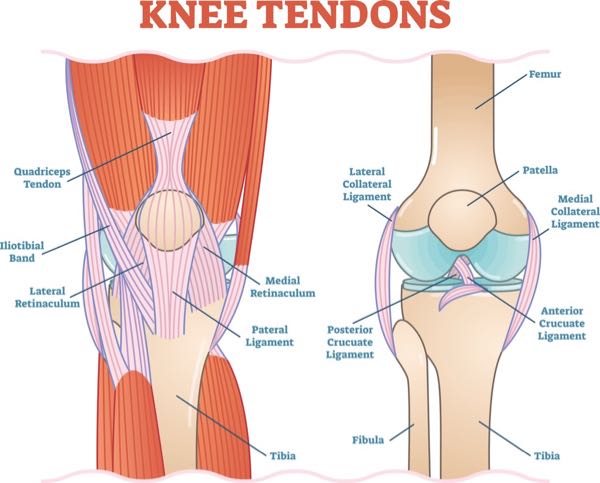

- Hinge joints are everywhere. Two significant examples are your knee and elbow. The long bones in your arms and legs are connected to each other via a hinge joint. It swings bones in and out in one direction.

You also have lots of hinge joints in your hands and feet. The bones in your fingers and toes are linked together through these types of joints. Think of making a fist or curling your toes. This movement is made possible by the collective effort of many hinge joints.

- When you turn your head, you’re utilizing a pivot joint. That’s because the first two vertebrae in your spine are pivot joints that make side-to-side head movement possible.

This joint type works by connecting the round end of one bone to another bone with a ring of ligament tissue. Pivot joints don’t allow 360-degree rotation, but they help you move a lot.

Another pivot joint is found at your wrist. The two bones in your forearm (radius and ulna) rotate around each other with the help of a pivot joint. Try turning your hand over to look at your palm and then the back of your hand. You’re utilizing this kind of joint.

- Ball-and-socket joints are the most mobile joints in your body. They have a large range of motion and can create movement in several directions.

These joints look exactly as described—like a ball in a socket. The spherical end of one bone fits into the cupped end of another. The two fit together very well and make it possible for the bone with the rounded end to move freely.

Your hips and shoulders are ball-and-socket joints. They help you swing your arms and legs in a front-to-back motion, and out to the side. You can also completely rotate the hip and shoulder.

Because these types of joints perform such dynamic movement they need protection from dislocation and injury. It is no surprise some of your strongest muscles surround ball-and-socket joints. Muscles, ligaments, and tendons power and stabilize the movement of these joints.

Joint Helpers: Ligaments and Tendons

Joints are powerful on their own, but they need help to stay in place. There are tissues in your body that secure bone to bone and bone to muscle. They’re called ligaments and tendons.

Tendons attach muscle to bone. They also protect the joints they surround. But the main role of tendons is to push and pull the bones they’re attached to.

Ligaments link bone to bone. Generally, the stronger the ligaments surrounding the joint, the more stable the joint is. That’s good. You want to maximize stability to ward off potential injury to your joints.

There are ligaments between the hinge joints in your fingers and knees. They strengthen the joints by preventing dangerous backward movement of the fingers. Ligaments also protect your knees from hyperextension (bending the wrong way).

Ligaments can decrease in strength and elasticity over time. So, it’s important to keep moving your joints that depend on the ligaments for stability. Maintaining your flexibility can support the long-term health of your joints.

Also, keep an eye out for signs and symptoms of joint injury. Unnecessary strain and overuse can leave even the strongest joints sore and swollen. Proper care for your joints includes regular use and rest. Give your joints a chance to recover from all the heavy lifting they do throughout the day.

Get Moving with 5 Joint Health Tips

Young or old, joint health should be high on your priority list. It’s never too early to start thinking about your joints. They work hard to move your body, so be good to them.

Joint discomfort is a pain, literally. But there are simple ways to keep your joints working and feeling their best.

You can stand up for your joint health by:

- Maintaining a healthy weight. Carrying around extra pounds adds stress to your joints. For example, when running you can put up to five times the force on your knee joints. That would mean for every extra pound or kilo of body weight you are carrying around would equate to an extra five pounds or kilos of force put on those joints. Many people experience moderate relief from joint pain by staying at a healthy weight.

- Exercising regularly. Moving the muscles that power your joints helps keep them from stiffening up. Low-impact exercises like walking, swimming, and biking are great ways to maintain joint health without intense aching or soreness. Protect your joints with proper safety equipment (like helmets and kneepads) before your sweat session. You only get one set, so treat it well.

- Improving your posture. Walking tall and sitting up straight don’t just boost your confidence. They protect your joints, too. Slouching and slumping put a lot of pressure on joints. Practicing good posture helps evenly spread the weight your joints carry.

- Eating Right. Fuel your muscles and bones with healthy foods to support joint health. Focus on getting calcium, magnesium, vitamin D, and other joint-health nutrients to support your bones. Dairy, canned sardines in oil (with bones), fortified cereals and orange juice, Chinese cabbage, and cooked kale will do the trick. And eat lean proteins for maintaining mighty muscles.

- Supplementing. Glucosamine and the omega-3 fatty acids in fish oil are key nutrients that support healthy joints. Consider adding these supplements to your daily nutrition to help maintain your joint health. Both are believed to also play a role in keeping up optimum joint comfort.

Take good care of your joints and enjoy all the fun things they make possible. Jump, spin, clap, or crawl—joints make it all possible.

About the Author

Sydney Sprouse is a freelance science writer based out of Forest Grove, Oregon. She holds a bachelor of science in human biology from Utah State University, where she worked as an undergraduate researcher and writing fellow. Sydney is a lifelong student of science and makes it her goal to translate current scientific research as effectively as possible. She writes with particular interest in human biology, health, and nutrition.

References

“51 ways to be good to your joints.” Arthritis Foundation.

“Anatomy of a Joint.” University of Rochester Medical Center.

“Anatomy, joints.” StatPearls.

“Bones, muscles, and joints.” KidsHealth.org.

“Caring for your joints.” WebMD.

“Simple tips to protect your joints.” Harvard Health Publishing.

“Structure and function of ligaments and tendons.” Washington State University.

“Synovial joints.” Lumen Learning.