The Immune System: Your Body’s Guards

Your immune system is in a battle every day. That’s its job.

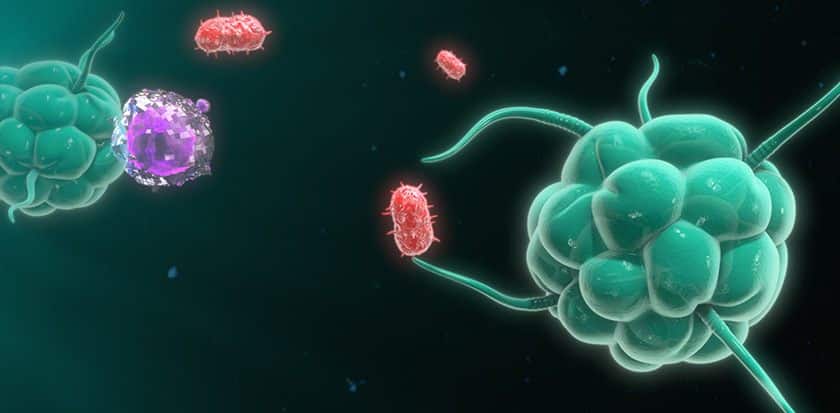

You’re protected by a coordinated defense. Cells, proteins, and chemical signals join forces against bacteria, viruses, parasites, and other pathogens. And your immune system also helps in wound healing, cellular and tissue turnover, and repair.

A healthy, functional immune system is a complex machine. It contains many layers, subsystems, tissues, organs, and processes. But a basic understanding can help you see what you need to maintain healthy immunity.

Barriers to Entry

Imagine your body as a castle to be defended. The first layer of defense are your physical and chemical barriers. They’re the high, thick walls that turn away many intruders.

Your skin is the most obvious physical barrier. And it’s a good one. Your largest organ is a waterproof covering that protects you against pathogens. Skin’s construction, substances on the surface, and other compounds in deeper layers help it provide protection.

Skin does a good job, but there are other paths into the body. That’s why other physical barriers exist.

Your upper respiratory tract has tiny hairs called cilia. They move potentially harmful material away from your lungs. Your gut barrier blocks absorption of possibly harmful substances. And your excretory (bathroom) functions physically expel pathogens.

Mucus blurs the line between the physical and chemical. Whatever category you put it in, mucus is an effective trap for invaders. It’s produced by membranes throughout your body. This thick, gluey substance is your body’s sticky trap, grabbing microbes and not letting go.

Other chemical barriers include: tears, saliva, stomach acid, and protective chemicals produced inside of cells and in your blood.

Immunity in General: Your Innate Immune System

The innate immune system is sometimes called the non-specific immune system. This subsystem of your larger immune defense is loaded into your genetic code. That’s the innate, or inherent, part. And it provides more general protection, destroying any microbes that enter your body. That’s the non-specific part.

Your cellular defenses kick in if a pathogen survives your physical and chemical barriers—which could also be considered part of the innate subsystem. That’s where phagocytes (a specific type of immune cell) come in. These white blood cells act like guards patrolling your body and destroying invaders.

These cells are found throughout the tissues of your body. They kill pathogens through a process called phagocytosis. It’s complicated, but there’s a simple way to understand it.

Phagocytes eat the invading microbes. They were named phagocytes for a reason—phago comes from the Greek for “to eat.” Phagocytes ingest or engulf the invaders. While trapped, several killing mechanisms are deployed to destroy the pathogen.

Some phagocytes have receptors that distinguish between healthy cells and potentially harmful substances. (They also deal with turnover of dead and dying cells.) Other pathogen eaters are chemically signaled to sites where they can be most useful. Phagocytes even help with the cleanup and repair after the invaders are destroyed.

Adaptive Immunity

Your adaptive immune system is like an immunity database. After encountering a specific pathogen, you have immune cells that can recall the best way to destroy it. That’s why it’s also referred to as specific or acquired immunity.

The original pathogen exposure can be intentional or accidental. That doesn’t matter. A normal, healthy response starts with an antigen. Think of an antigen as the bar code of each cell. Just like every item in the grocery store has a unique bar code, each cell type has a unique antigen code to identify it.

These antigens—mostly proteins—can also identify pathogens. Our immune system has learned to read these antigen codes. When they recognize something as being foreign, they initiate an immune response.

Each unique antigen triggers the creation of a unique antibody. The y-shaped antibody binds back to the corresponding antigen and marks the invader for attack by other immune cells. Some antibodies can even take care of business for themselves.

Lymphocytes (another specific type of immune cell) are the main cells involved in your adaptive immune system. Two types of white blood cells—T and B cells—are produced in your bone marrow. They can attack and kill pathogens on their own, or assist other white blood cells in the responses.

T and B cells form the basis for your body’s immunity memory bank. B cells present antigens and create and release antibodies. Memory T cells—those that survive previous attacks—quickly and effectively respond to known pathogens. Together, they help your immune system efficiently and effectively destroy known bacteria, viruses, or other pathogens.

Defend Your Immune System

Above, you’ve read about the way a normal, healthy immune system functions. But your defenses can be impacted by your environment, diet, stress, sleep, travel, and other lifestyle factors.

Healthy immune function is a whole-body effort, and maintaining it takes a holistic approach. Here’s a few things that can help:

- Get at least seven hours of sleep a night—and avoid pulling any all-nighters.

- Exercise regularly to promote memory cells, enhance skin immunity, and mobilize immune cells.

- Minimize stress as much as possible or practice healthy coping strategies, like exercise.

- Eat a healthy, balanced diet full of fruits, vegetables, and lean proteins to provide essential micro- and macronutrients and important phytonutrients. A healthy diet (that includes healthy amounts of fiber) will also provide your microbiome with what it needs to maintain good gut barrier function.

- Practice good hygiene, including frequent handwashing, so your body doesn’t have to deal with as many pathogens in the first place.