The Gut-Brain Axis: Connecting Your Brain and Microbiome

The brain is often talked about as the master of the body. It sends messages along the information superhighway of the central nervous system. This turns electric impulses and thoughts into action and behavior. The brain is like the Wizard of Oz: it’s the ring leader behind the curtain, directing the cognitive processes and movements of the body.

However, in recent years, scientists have found that the brain doesn’t act as independently as once believed. Careful studies show there is another major player aside from the brain. And a curious one at that. In fact, this other player isn’t a sole entity at all, but rather trillions of microscopic ones. It’s a system of trillions of bacteria and other bugs, known as your gut microbiome.

Here’s another way to look at it: Say the brain is the CEO of the company known as your body. That would make your microbiome the extensive members of the company’s staff. Having a good, connected working relationship between employees and the CEO creates success. But just like a company run with zero input from its staff, a body run solely by the brain misses out on essential messages and signals that would contribute to an ideal functioning body.

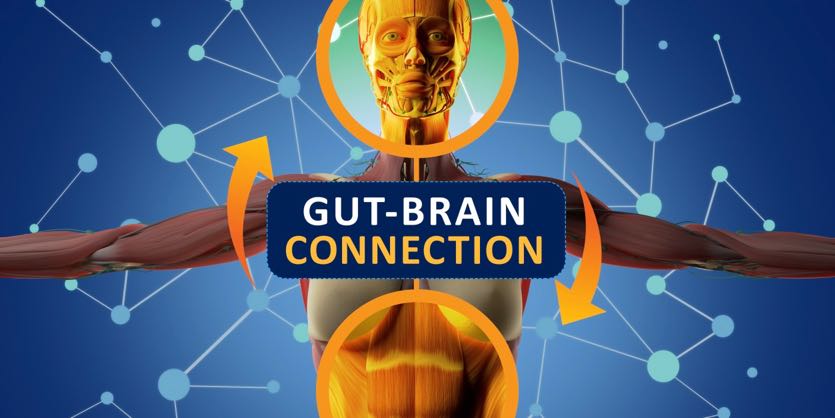

To avoid such tyranny, the body has coevolved alongside intestinal bacteria and other bugs. This makes the relationship between the microbiome and the brain an intertwined one. It’s a mutually beneficial partnership based on regular communication between the brain and microbiome. The two speak through a variety of mechanisms to maintain the health and well-being of your body. This crosstalk between the two affects hunger, digestion, and satiety, as well as your immune and mental health.

In order to appreciate how your microbiome can affect your brain, let’s gain an understanding of the microbiome. Then we’ll look at how it works together with the brain. First, let’s focus on the bacteria and other bugs. To answer: What exactly lives in your gut and why?

The Microbiome: Your Body’s Bacteria And Other Bugs

Your gut is home to trillions of little bugs known collectively as the microbiome. These microorganisms (including bacteria, fungi, viruses, protozoa, and other bugs) make up the community that resides there.

Microbiota is often used interchangeably with microbiome. You’ll see the term microbiome used more here because it stands for much more than the bugs themselves. “Microbiome” encompasses the entire community of microorganisms along with their functionality and activity in the gut.

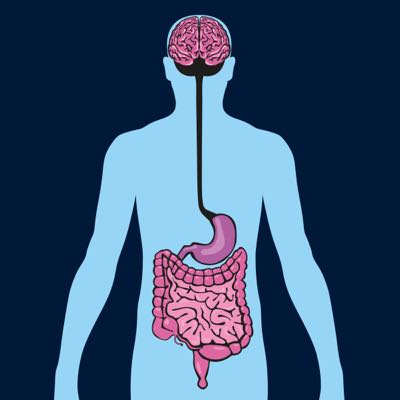

Many of the functionalities of your gut microbiome occur there, in your intestines. However, there are interactions between those bugs and other parts of the body that act as communication mechanisms between the microbiome and the brain. Let’s learn more about these interactions that make up the gut-brain axis.

Your Brain On Bugs—Gut-Brain Axis Basics

As mentioned before, your brain and microbiome constantly communicate. This link is often referred to as the gut-brain axis, or GBA. Communication along this line is essential to maintain homeostasis—or balance—in your gut and elsewhere. There are various routes of communication that constitute the GBA. But the most prominent is the vagus nerve. It’s involved in digestion and healthy gut immune response, among other bodily processes and reactions.

Digestion

The vagus nerve is a cranial nerve that starts in the brainstem and runs down to the large intestine. This nerve covers so much ground within the body that it’s no surprise that the vagus nerve is responsible for regulating a number of internal functions. Some of these are digestion, respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, some immune responses, and several internal reflexes (e.g., sneezing and swallowing).

Digestion is the first topic to chew on.

Research has shown that the gut isn’t just the site of digestion and nutrient absorption. The gut is also the mediator between its microbiome and the brain. Basically, the gut witnesses the processing of the food you consume. Then it reports relevant information from that process to the brain via the vagus nerve.

As the site of food digestion, the gut has immediate knowledge of what is being consumed. It gathers information about nutritional and energy content. The vagus nerve makes sure the brain stays up-to-date on this sensory information, like hunger cues and feelings of fullness.

This knowledge is important for the brain, so it can determine:

- How to drive related impulses (e.g., telling your brain your gut is full and therefore you should stop eating).

- How to shift your mood (e.g., if you’re hungry, your mood can become irritable).

- Where it is best to send energy (e.g., when you are cold, energy is sent to warm your most vital organs).

Relaying Immune Reflexes

The vagus nerve also communicates other gut events to the brain. Along with the ingested food comes allergens and other microbes that can activate normal immune responses in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Even though they are typical, healthy responses, these reactions can occasionally and temporarily get in the way of regular gut function.

Your brain needs to know about these minor inconveniences. So, this information is “sensed” by the gut and carried to the brain by the vagus nerve on the information superhighway of the gut-brain axis. The direction of information described above is referred to as an “afferent” pathway. That means messages travel away from the gut to the brain.

Gut-brain axis communication helps provide your brain—and eventually the rest of your body—with information it needs to mount and maintain a proper, healthy response. The communications from the brain to the gut are along what’s called “efferent” pathways (working in the opposite direction from the afferent pathways). They work when the efferent fibers from the brain send signals back down the vagus nerve to help maintain and support a healthy, normal immune response.

You Are What You Eat

It’s important to consider how to keep your gut and brain healthy in order to maintain quality communication between both along the gut-brain axis. The easiest way to do this is through food and nutrition. And you have at least three opportunities each day to influence what goes into your gut.

Your microbiome acts as a mediating factor between lifestyle choices—like diet—and the maintenance of health. What you eat enters your body and may alter the bacteria found in your gut. The effects of this can be positive or negative on processes like digestion. And changes to these processes can either maintain or hinder your health. Let’s take a closer look.

Diets rich in plant-based protein and fiber tend to increase the abundance of bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Lactobacillus. These are beneficial bacteria that tend to maintain health in your gut. Conversely, diets rich in animal-based protein and saturated fat could increase the abundance of Bacteroides and Alistipes, which are thought to be associated with cardiovascular and bowel issues.

Additionally, studies show that those who consume more vegetables and less fat tend to have a more diverse microbiome with many different beneficial bacteria represented. And those who consume a high-fat diet tend to lack bacterial diversity in the gut, which isn’t good for your digestive health.

While the community of bacteria within your gut is complex, keeping it healthy can be rather simple. Beneficial bacteria prefer to eat certain types of food that tend to get labeled as “healthy” or “healthier.” The opposite is true for bad bacteria: they prefer to eat the things you should eat in small amounts, like saturated fat. So, when you sit down to eat next, ask who you would rather feed—the good or the bad bacteria?

Here are some tips to consider:

- Minimize your intake of saturated fats. Unsaturated fats like olive oil and avocados promote the healthier bacteria like Bifidobacteria and Saturated fats tend to increase Bacteroides, the bugs that negatively impact gut health.

- Increase your intake of fiber-rich vegetables. These foods contain many complex starches and fiber your body can’t break down completely on its own. Instead, your body relies on the gut bacteria to break down some of the fiber. In the process, the bacteria create short-chain fatty acids that support gut health. These fiber-rich foods act like prebiotics, feeding your microbiome.

- Consider adding probiotic foods to your diet. Probiotics support a healthy balance of beneficial bacteria to your gut. Find a tasty yogurt that you like, and keeping your gut healthy will feel like a sweet treat! If dairy isn’t your thing, you can try fermented foods like sauerkraut, kimchi, or sourdough. And probiotic supplements are also a great way to help you find a beneficial balance of gut bacteria.

Minding Your Microbiome

Your microbiome is a complex system that’s ready to help you live your best life. It does so largely through digestive processes, but also by relaying important messages to your brain. Maintaining a happy gut keeps communication along the gut-brain axis flowing. And together, this powerful pair helps support your overall health.

About the Author

Jenna Templeton is a health educator and freelance science writer living in Salt Lake City, Utah. After receiving a bachelor of science degree in chemistry from Virginia Tech, Jenna spent five years as a research scientist in the nutritional industry. This work fueled her interest in personal wellness, leading her to pursue a graduate degree in Health Promotion & Education from the University of Utah. Outside of work, Jenna enjoys live music, gardening, all things food, and playing in the Wasatch mountains.

References

Agusti A, Garcia-Pardo MP, et al. (2018). “Interplay Between the Gut-Brain Axis, Obesity, and Cognitive Function”. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 12: 155.

Carabotti M, Scirocco A, et al. (2015). “The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems.” Ann Gastroenterol. 28 (2): 203-209.

Bischoff SC. (2011). “‘Gut health: a new objective in medicine?’” BMC Medicine. 9: 24.

Breit S, Kupferberg A, et al. (2018). “Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders.” Frontiers in Psychiatry. 9: 44.

Foster JA, Rinaman L, Cryan JF. (2017). “Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome.” Neurobiology of Stress. 7: 124-136.

Houghteling PD, Walker WA. (2015). “Why is initial bacterial colonization of the intestine important to the infant’s and child’s health?” J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 60 (3): 294-307.

Quigley EMM. (2013). “Gut Bacteria in Health and Disease.” Gastroenterol Hepatol. 9 (9): 560-569.

Singh RK, Chang H, et al. (2017). “Influence of diet on the gut microbiome and implications for human health.” J Transl Med. 15: 73.

Young VB. (2017). “The role of the microbiome in human health and disease: an introduction for clinicians.” BMJ. 356:j831.